John Paul Morabito

Name: John Paul Morabito

Studio location: Chicago, unceded homelands of the Council of Three Fires

Website / social links: johnpaulmorabito.com , @johnpaulmorabito

Loom type or tool preference: TC2 Digital Jacquard / 16 Shaft Toika Horizontal Countermarche

Years weaving: 20

Fiber inclination: Whichever the form calls for, I’m promiscuous.

Current favorite weaving book: Anni Albers: On Weaving

1. How did you discover weaving and was what your greatest resource as a beginner?

When I graduated high school, Barbara Allen (who first taught me to weave) gifted me a 1965 copy of On Weaving by Anni Albers. I’ve since read the text cover to cover many times and continue to turn to it in my teaching and research. As a unified whole, On Weaving functions as a technical guide and ideological tome. This was instrumental to my making early on. While weaving classes weren’t an option during my foundation year of art school, I stubbornly found a way to incorporate it into everything I did. Turning to Anni Albers’ algorithmic descriptions, I hand-picked weaves on improvisational looms until I could access a floor loom. As I speak of the importance of Anni Albers, I must acknowledge the coloniality within Modernist weaving. Foundational figures such as Anni Albers, Ed Rossbach, Sheila Hicks, and Lenore Tawney drew upon knowledge unearthed from Pre-Colombian textiles with a gaze that cannot be separated from Primitivism. If we are to move forward, as a discipline, we must face this colonial legacy.

2. How do you define your practice – do you consider yourself an artist / craftsperson / weaver / designer / general creative or a combination of those? Is this definition important to you?

Weaving encompasses many domains; art, design, craft, and engineering. While I believe that all weaving involves a mixture of these approaches (we consider the visuality of a woven surface in concert with the architecture of cloth), there is the matter of how the work exists in the world. Our understanding of an image/object as art, craft, or design influences our approach and encounter with the form. These domains have meaning. With this understanding, it is important to consider my practice within the context of contemporary art. The role of an artist, I believe, is to bear witness to and reflect humanity, to make meaning for a public. As an artist, my weaving is of me, but it is not for me.

3. Describe your first experience with weaving.

I was introduced to weaving in high school. It was a public-school art program (oh the things we made with cardboard and brown paper…) and craft had a strong presence. My teacher, Barbara Allen, taught me on 4 shaft table looms she brought from her own studio. This seemingly small gesture defined the path of my life and for that I am deeply grateful. With that first weaving, I had no real understanding and went into the process without intention or expectation. From there, with a beginner’s mind I was able to listen to the process and explore. Weaving, in my understanding, is distinct from other textile arts. Beyond the significant technical complexity, being a weaver is an identity. I really connected to the weaving identity that first time with a loom. Once I began something sparked; it was all I wanted to do.

4. What is your creative process, from the initial idea to the finished piece? Are there specific weave structures, looms, or fibers that are important to your process?

Mediated improvisation is central. In my weaving, mediation becomes immediate through submission to the systematic limitations of the loom. Once there, I can work freely. To realize woven live-form, I engage an oxymoronic union that merges the predictable logic of digital weaving with improvisational making. The immediacy of live-form has been essential to my Magnificat tapestries. With Magnificat, I employ High Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and Child as cartoons which I render faithlessly. Introducing the mixture of colorful threads live at the loom, I actively mutate these paintings into woven images that recall their origins even as they become something new. Through such visual mutation, the Magnificat tapestries manifest the co-presence of Italian painterly modeling and digital mediation. Thus, my tapestries present a queer anachronism as they waver between the ancient and the modern. They are retrograde and latter-day, decadent and pious, holy and blasphemous.

5. Does your work have a conceptual purpose or greater meaning? If so, do you center your making around these concepts?

I am only interested in making work with meaning. However, meaning is not monolithic. Improvisational making lends an unpredictability to the form that produces a subsequent elasticity of meaning. I’ve learned to trust that my aesthetic sensibilities will inflect conceptual and political intentionality upon the work. Centering sensibility creates an ambiguity that makes space for many perspectives. I don’t want to tell viewers what to think, I want them to consider the dialectics. Any resulting ruptures or divergences are themselves catalysts for meaning that reflect the encounter of different positionalities. While the didactic has its place, it certainly doesn’t engage me. I’m not interested in making work that relies upon or maintains a singular interpretation. Rather, I’m motivated by the slippages and multiplicities of meaning.

6. What is your favorite part of the weaving process and why? What’s your least favorite?

It’s not exactly a process, but I find the positionality of textiles to be both infuriating and engaging. Weaving provides social meaning through its orientation as adjacent to (but outside of) art. Even amidst a contemporary renaissance, its positionality is marginalized. While navigating disciplinary legitimacy and de-legitimacy is frustrating, I also see this as a site of meaning. Tapestry, once considered the highest of arts, is now situated tangentially. Drawing upon this fall from glory, the medium presents an opportunity to queer sacred iconography.

7. Do you sell your work or make a living from weaving? If so, what does that look like and how has that affected your studio practice?

Since 2007, weaving has been my means of making a living. I began my career working as designer in the New York studio of Suzanne Tick. At Tick Studio, the textile was a platform to envision new material possibilities. As the studio weaver, I invented woven constructions through a process of speculative weaving. This foundation engendered specialized knowledge which continues to serve as a vocabulary. Today, as an artist who is a professor, I continue to make my living through the loom. That my weaving is public-facing brings a responsibility for technical acuity, conceptual articulation, and relational consideration.

8. Where do you find inspiration?

My work employs exquisite craft and visual decadence to mirror the sincerity of faith with queer sensibility. I grew up in a New York Italian third culture. While my family has been in the United States for three generations, we have stubbornly refused to let go of our ethnicity. Queerness creates a liminal partiality that places me within and outside of this particular group identity. Navigating that has become a central strategy in my making. Italian people have been Catholic for 2000 years. While the orthodoxy of this cultural legacy is deeply ostracizing, it is also a bond I cannot and will not deny. Accordingly, I am working aesthetically to respond to the antagonistic encounter of queer space and sacred space. The Catholic Imagination, as manifested by Italian American immigrants, creates an aesthetic landscape defined by tacky opulence. I think often of the parallels between my grandmother’s living-room recreation of the Vatican and the exaggerated glamor of a drag queen. This is the aesthetic sensibility I am working with; it is ethnic and sacred, and decadently queer.

9. What other creatives do you admire – weavers, artists, entrepreneurs – and why?

As we navigate a global pandemic, I find myself thinking of Félix González-Torres. During the horror that was the AIDS crisis, González-Torres bore witness to queer humanity. He spun grace and desire into an inseparable form, redirecting the essential carnality of Catholicism into coded representations of the personal and body politic. I see his work as a queer and ethnic tangent in which Catholic sensibilities are manifested within conceptual art strategies. As a queer, Catholic artist working a generation later, my weaving might act as an anachronistic, adjacency that draws sensibilities of queer conceptual art into the realm of craft.

10. If you could no longer weave, what would you do instead?

Weaving is the wholism through which I am working. Through the loom, my practice expands to encompass image-making, new media, performance, relational and social practices, writing, and industrial design. I am always weaving, regardless of the materials or processes. Suffice to say, I’d still weave if I could not weave, just in a different way. Weaving is the wholism.

Do you have any upcoming exhibits, talks, or events the community should know about?

My work is on view at the Musée des Maîtres et Artisans du Québec in Montreal in an online exhibition of works from the permanent collection as part of Virtual Museum Canada. Over the next few months I will be presenting online lectures through a number of venues including the 2021 College Art Association Conference, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago Department of Fiber and Material Studies Mitchell Lecture Series, and the Textile Study Group of New York.

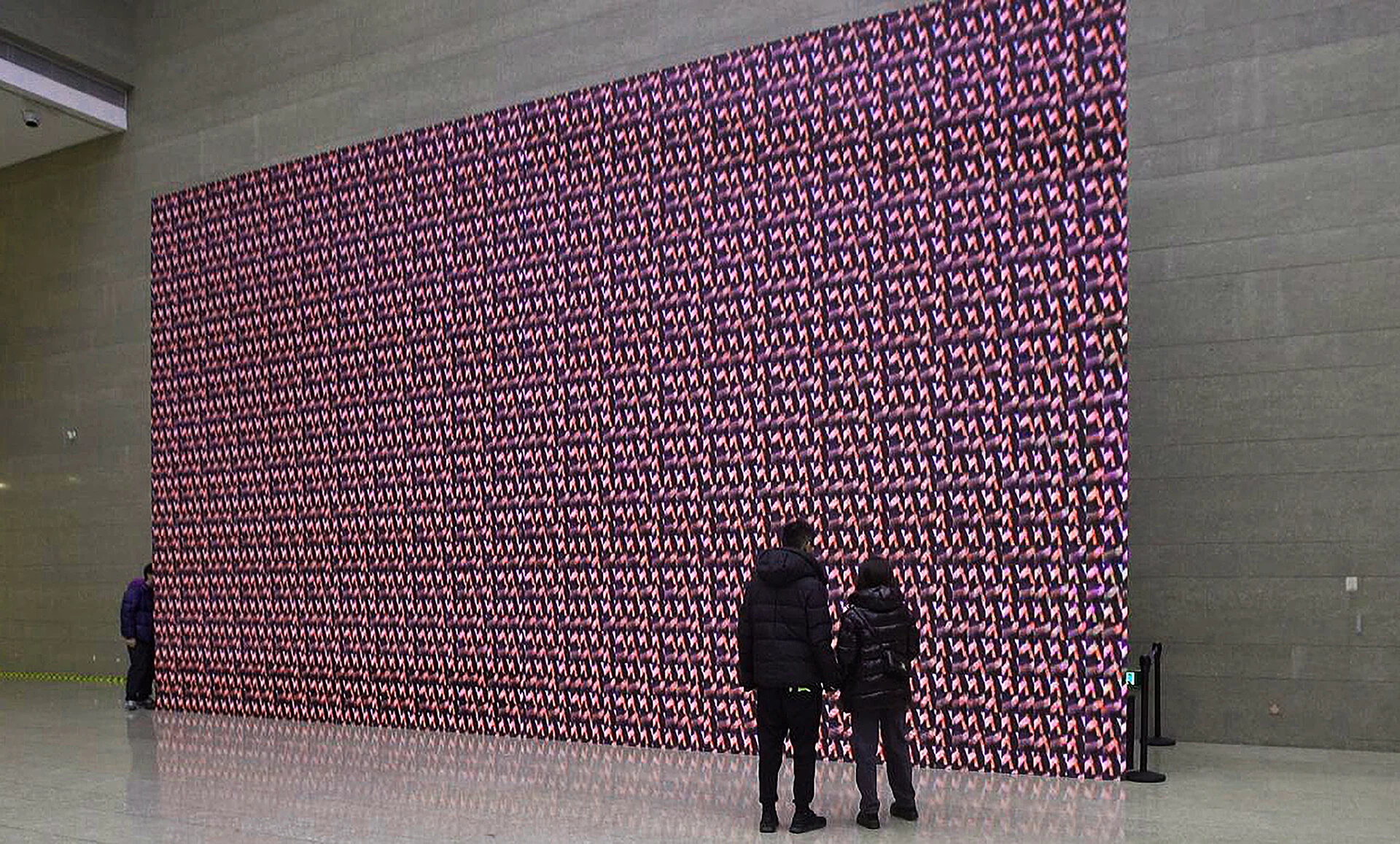

Photo credit: Ian Vecchiotti